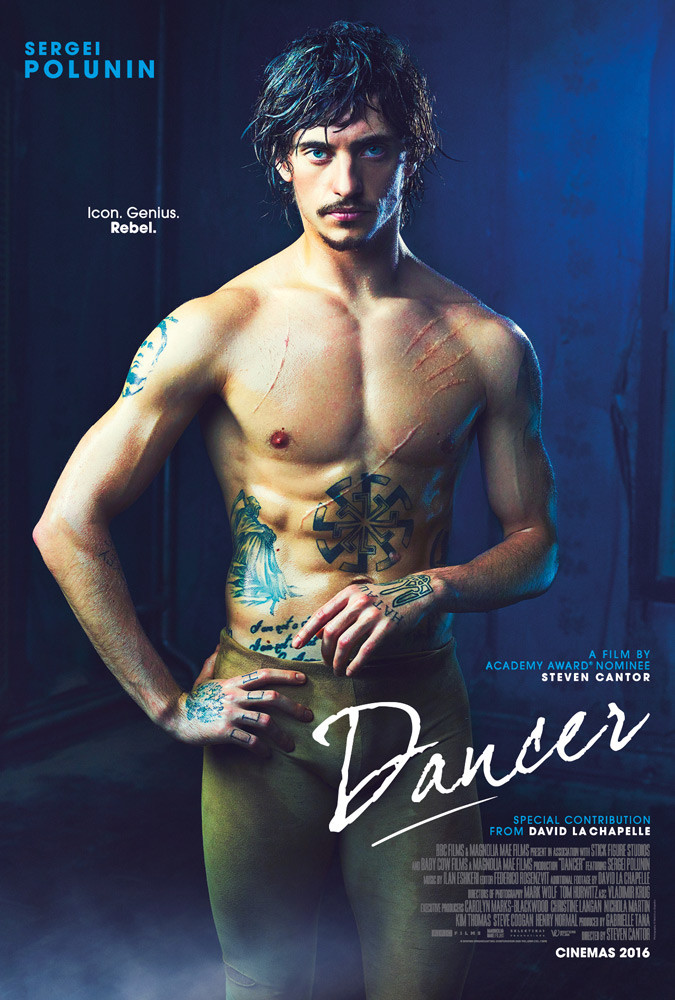

Sergei Polunin (1989.11.20) /烏克蘭。

之前看了TAKE ME TO CHURCH時,對Polunin所散發出的特質及抑鬱到爆的氛圍(不是舞作的關係)感到 “不可思議”。透過這部紀錄片後,終於了解 …. 我很喜歡這部紀錄片。

一旦失去目標夢想的背後意義,夢想再也不會是夢想 ……

為誰而跳 ? 夢想追逐的最終,想成就的是什麼 ?

與生俱來的才華,加上後天的努力,13歲就開始考上英國皇家芭蕾舞學院,19歲前就完成所有芭蕾訓練、卓越的技巧及完美的舞姿,讓他成為舞團史上最年輕的獨舞者。這看似一切順利、其他舞者夢寐以求的際遇卻讓他非常不快樂,因為最親愛的家人,為了支付他的學費,他的父親與祖母需到異地工作,而父母親在他赴英國一年後因故離婚,原先窮但充滿快樂的家庭,因為他而破碎、分離,他也因無法有能力讓家人一起而傷心、難過。22歲,宣布退出舞團,震撼舞蹈界、舞迷 ….. 舞台上的光環有多亮、承受的身心壓力就有多大,更何況成為獨舞者時,他才19歲 !

沒有家人的異地生活、異地語言、文化、習慣的適應、當你有苦悶無法向了解你的家人傾訴、快樂時無法與家人分享時,那種身心靈上無法獲得的踏實感是令人倍感煎熬的 … 沒有了踏實感,一切都是空。有些部份,若沒有親身經歷長期異地生活的人是很難體會的。在這部紀錄片,可以看到Polunin的自我探索 ~ 蠻感動的 …。

現在的Polunin比之前開朗、快樂許多了喔。2013年加入英國皇家芭蕾舞團的首席舞者-俄裔芭蕾伶娜 Natalia Osipova在2015在準備吉賽爾舞作時,找不到適合的舞伴,在她媽媽的建議下,她寫一封EMAIL給Polunin詢問他是否能當她的舞伴,沒想到Polunin一口答應,呵,當然接下來的發展就是…………目前芭蕾舞界最受注目的Couple ……「吉賽爾」果然魅力無窮阿 ~ ~ 呵。 目前兩人將著手準備當代舞作品於2018年英國沙德勒之井劇院一起演出。

■

Dancer was screened on 8/9 October as part of the London Film Festival 2016

USA release: 16 September 2016

UK release: 6 March 2017

Dancer on IMDb

Dancer, the documentary film about Sergei Polunin (part funded by the BBC) was launched in the United States last month but won’t go on general release in the United Kingdom until 6 March next year. It will be available on DVD and Blu-Ray. It has been given a few screenings in London, most recently as part of the BFI London Film Festival, with Polunin and the director, Steven Cantor, in attendance for Q&A sessions.

The producer, Gabrielle Tana, had suggested filming the ‘troubled prodigy’ soon after he left the Royal Ballet in 2012, in order to reveal the discrepancy between his Bad Boy of Ballet public image and his private self. She and the rest of the documentary team (credits include seven executive producers and five associate producers, as well as the technical crew) took years to win the trust of Polunin and his estranged family.

The arc of the biopic was to be young Sergei’s early promise as a ballet dancer in his native Ukraine, his meteoric rise within the Royal Ballet, his defection and finally, his decision to give up dance altogether. But, as we know, he didn’t. He was encouraged by the filming of his ‘farewell’ video, set to the song ‘Take me to Church’, to change his mind. The video (filmed by photographer David LaChapelle) went viral last year, boosting Polunin’s career prospects and inspiring hosts of imitators, from small children to a guy in his garage.

The documentary ends prematurely, with a brief coda after the spectacular video to show Polunin reconciled with his mother, father and grandmothers. His current partner, Natalia Osipova, is to be seen only by those in the know, reflected in a mirror. They had just got together when the filming took place after a gala in Moscow. So it was left to Polunin in person to bring us up-to-date with his plans – of which more later.

The documentary starts with the tattooed dancer bare-chested, head bowed, breathing heavily as he sits back on his knees. He must be preparing for yet another exhausting take of the video. Members of the crew pass in front of the camera, seemingly indifferent to his state of distress – a foretaste of what is to be revealed about his life so far.

After the inevitable hype about Polunin being the world’s greatest dancer, the enfant terrible of the Royal Ballet, we are shown his origins. His Russian-speaking family come from the city of Kherson in southern Ukraine, filmed in winter to look utterly desolate. His mother tells how supple little Sergei, talented at gymnastics, then ballet, was to be their hope of a better future.

They made sacrifices so that he could go to the Kiev State Ballet Academy. His mother, Galina, who pushed him hard, decreed that he must study abroad, and applied for an audition at the Royal Ballet junior school. Her decision is not explained. The Kiev school has a fine reputation, as do the Bolshoi and Vaganova academies: Galina evidently wanted a route to the West.

Video footage of Sergei as a youngster, probably taken by his mother, reveals how gifted he was – and how joyous. His and her excitement at coming to London and seeing the White Lodge ballet school is soon tempered once he is accepted at 13, on a scholarship from the Rudolf Nureyev Foundation. ‘Everybody parted like ships at sea’, says his grandmother, sadly. To fund Sergei’s training, she had sought work in Greece; his father, who had gone to work in Portugal, then split up with Galina, who was back in Kherson. They divorced when Sergei was 15, already the outstanding student in his Royal Ballet class.

He had worked hard to justify his family’s faith in him, but couldn’t keep them together. He despaired: ‘I wasn’t able to make everything fine and good.’ He partied hard with his schoolmates, passing out swiftly after binge drinking. According to his friends, Jade Hale-Christofi and Valentino Zucchetti, this was adolescent fun. Sergei would get so out-of-it that they filmed themselves painting his face and shaving off an eyebrow before he was due to perform in a competition.

His dancing doesn’t seem to have suffered, though his defiant behaviour and psychological state should have been addressed by the school. He had even less guidance once he was accepted into the Royal Ballet company and made its youngest male principal. (Tetsuya Kumakawa had been a few months older when he was promoted to principal.) The media were tipped off that the Royal Ballet had a phenomenal dancer in its ranks. Arts correspondents and other journalists, as well as critics, were invited to Polunin’s performances.

Meanwhile, his parents were unable to see him dance. He had banned his mother because he was angry with her; his father couldn’t get a visa. ‘What’s the reason for me dancing any more?’ Polunin wondered, according to Zucchetti. The media soon cottoned on to the ‘troubled star’s’ drinking, drug-taking and growing number of tattoos. (He had taken part-ownership of a tattoo parlour.) In January 2012, Polunin walked out of a bad rehearsal and announced that he had quit the Royal Ballet. Cue newspaper headlines and TV coverage.

He was a disturbed youngster badly in need of help, his own worst enemy in the disciplined world of ballet. He was making himself unemployable. ‘I had to go to Russia’, he said, ‘which was not in my plans.’ Why not? He was rescued by Igor Zelensky, artistic director of the Stanislavsky and Novosibirsk ballet companies, who became a substitute father figure. He gave Polunin leading roles in his companies’ productions, which included several MacMillan ballets as well as the classics and the Soviet Spartacus.

What footage there is in the documentary of Polunin in major roles comes from this period. The film director wasn’t interested in how he danced, other than to capture flashy steps. Glimpses of his roles were selected to illustrate his mental states: Albrecht in Giselle Act II for sombre thoughts; Rudolf in Mayerling for drink and drug taking; Spartacus for suffering. Filmed backstage during a Novosibirsk performance of Spartacus, Polunin is presented as an exhausted rock star. Semi-naked, covered in tattoos, knocking back stimulants, rude to his female dresser, he goes back on stage to be martyred to ecstatic applause.

He looked unwell, gaunt, lacking stamina and probably resentful of the film crew’s presence. ‘Why do you have to do anything just because you’re good at it’, he complained: ‘Ballet makes you a prisoner to your body and the urge to dance.’ With the crew, he went back to dreary Kherson to confront his mother in a carefully set-up encounter, and visited his first ballet school. He was then shown meeting Jade Hale-Christofi in California in order to request choreography for his last-ever dance. In fact, the video had already been filmed some time before. The time-scale is all over the place – and there is no mention of Polunin pulling out of Peter Schaufuss’s Midnight Express in London (in 2013) and the subsequent legal case for breaking his contract.

According to Hale-Christofi, the ‘Take me to Church’ solo was intended to reveal his friend Sergei’s inner demons, and the conflicts tearing him apart. (The angry protest song, by Irish musician Hozier , was chosen by LaChapelle.) The four-minute video, released in February 2015, was filmed over many hours in an airy wooden chapel-like building in Hawaii. By then, Polunin had regained his energy and his passion for dancing. The sensational solo shows him hurling himself across the sunlit space, leaping and tumbling, clutching his head and shoulder in simulated anguish. Unlike the dancing footage in the rest of the documentary, it is artfully filmed and edited.

Some time later, having shaved his head and added yet more tattoos, Polunin agreed to perform in a gala in the Stanislavsky theatre (as did Osipova). At last his family saw him dance. The credits roll over yet more moody shots of him in action for the camera, accompanied by tempestuous music. What will his future hold?

Answering questions from the audience after the London Film Festival screening, Polunin said that he and Osipova plan to set up their own foundation, Project Polunin, to enable dancers to broaden their careers. They would be put in touch with agents, lawyers, financial advisers and contacts in other industries – fashion, music, movies. He aims to make videos that modernise the visuals of classical ballet, in the way LaChapelle has done with ‘Take me to Church’. He has auditioned successfully for a film, due to start this December. He wouldn’t be drawn on what it is to be about, nor whether he might be able to return as a guest with the Royal Ballet.

Although Polunin, at 27, appears to have grown up a lot since he walked out of the Royal Ballet, he still seems in search of an artistic identity. He wants to be famous, ‘to do as many things as I can’. He talks about ballet as an industry that exploits dancers without being able to reward them as generously as footballers or film stars. Does he believe he could be another Nureyev, highly paid as a perpetual guest artist? Or a Baryshnikov or Sylvie Guillem, spanning ballet and contemporary dance? Or a David Beckham, athlete, model and business man? The documentary shows how vulnerable he is, how much in need of a support system. Will he find one?

( By Jann Parry on October 15, 2016 )

*

*

*

*

*